FT BR: Crackdowns, lawsuits and intimidation: the threat to freedom of expression in India.

Big Read

A clamorous public square has long been a point of national pride. But the pressure on unfettered speech is palpable.

The income tax officials arrived at the Bangalore office of the Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation on Wednesday, September 7, and stayed until 4:30am on Friday. They combed through records, took statements from senior staffers and removed the organisation’s laptops and mobile phones to clone the data. As they worked through the first night, the chief executive, Sunil Rajshekhar, caught a few hours’ sleep in his office.

Across India, in the capital of Delhi, tax inspectors were simultaneously swooping on two more non-profits: Oxfam India and the Centre for Policy Research, a sober think-tank known for holding debates and publishing papers on such worthy topics as health and nutrition, federalism, and the regulation of India’s urban trees.

During what Oxfam described in a statement as “35-plus hours of nonstop survey”, staff were not allowed to leave the building, the internet was cut off and their mobile phones confiscated. Oxfam said the tax team removed hundreds of pages of data pertaining to its finances and programmes, and cloned its server.

The crackdown was not uncommon for India, where fiscal and law enforcement agencies are known for conducting regular — and, critics say, overzealous or politically motivated — searches of individuals and organisations, from opposition politicians to Chinese smartphone makers. In 2020, Amnesty International was forced to suspend its operations in India after its bank accounts were frozen following the human rights group’s criticism of Narendra Modi’s government.

Yet it was the nature of the groups targeted this time that sent a chill through civil society. While the IPSMF supports independent news outlets that have faced intensifying legal and public pressure since prime minister Modi took power in 2014, Oxfam India and the CPR have no such connections. All three organisations declined to comment for this story.

The searches were part of what liberal Indians decry as a clampdown on freedom of expression that, they say, has widened beyond media organisations and journalists to public intellectuals, think-tanks and comedians, too.

“There seems to be a new strategy of claiming financial impropriety — not just for journalists, but for other civil society organisations,” says Naresh Fernandes, co-founder and editor of Scroll, a news website. “It immediately cloaks what is essentially a political attack and has been used against civil society and opposition politicians . . . Once you raise the spectre of corruption, it’s easier to get public opinion to fall in line.”

India’s clamorous public square and disquisitive journalistic and intellectual culture has been a point of pride for many citizens. But the pressure on unfettered speech in the world’s largest democracy is palpable. Lawyers, journalists and activists say they see editors and reporters increasingly pulling their punches on topics that risk landing them in trouble. Even as the country moves to portray itself as a counterweight to an increasingly authoritarian China, rumours of self-censorship extend to people in business, with potentially harmful consequences for the development of the world’s fifth-biggest economy.

“Fewer and fewer people want to speak, and for good reason: there are consequences,” says Vrinda Grover, a human rights lawyer practising in India’s Supreme Court. Grover serves as defence counsel for the journalist Mohammed Zubair, co-founder of the non-profit fact checking website Alt News. His arrest by police in June over a 2018 tweet “hurting religious beliefs” — and subsequent multiple charges including criminal conspiracy, destroying evidence and receiving foreign funds — made headlines around the world.

Government officials reject the notion of any such crackdown. Instead, they ascribe the complaints to an entrenched culture of entitlement and access among liberal journalists and opinion-makers, which has been swept aside in a new India ruled by a popular, twice-elected prime minister whose supporters have pushed the old elites to the margins.

While some Indian media described September’s tax inspections as “raids”, the government rejects this description. “I believe the technical term was ‘survey’,” says Kanchan Gupta, a senior adviser with India’s Ministry of information and broadcasting. He adds that the Modi government is “tough” in enforcing a new law restricting foreign funding for Indian NGOs, and that he understands the survey was meant to check the groups’ compliance with it and tax law.

“Central government does not take punitive action against journalists,” he says. “Some state governments are known to have done that, as it is their domain; in many cases the action is not linked to their journalism, but to other activities.”

Like others in the ruling camp, Gupta says media groups have failed to keep up with the popular will of a changing India. “Media owners are angry because their fat-cat editors are no longer door openers and editors are unhappy that they are no longer door openers because that puts their jobs on the line,” he says. “That culture has changed . . . If that doesn’t work for some of the journalists — tough luck.”

Sedition and defamation:

The most sinister example of curtailment of freedom of speech in many Indians’ living memories happened in the 1970s, when then-prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended democratic rights and imposed rule by special powers for almost two years. During that bleak period, known as “the Emergency”, journalists were jailed, editors were required to vet stories with the government and press freedom was suspended outright.

Some in India’s besieged press corps have made comparisons with that time. But others dismiss the analogy as overdrawn in Modi’s India, which has a diverse range of outlets and voices, including the digital upstarts the IPSMF has been funding.

With lower overheads and donations from private individuals, nimble digital outlets have managed to avoid the pressure increasingly faced by mainstream media from corporate or government advertisers to toe a non-confrontational editorial line, says Apar Gupta, executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation. “The established media have become more corporatised and more dependent on corporate and government advertising,” he says. “They have always been beholden but the pressures have increased.”

Online news sites have been unsparing in their coverage of some of the more draconian interventions of the present government’s first two terms — from the overnight demonetisation of more than 80 per cent of the currency in 2016, to the strict national lockdowns imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic, which sent millions of urban migrant workers trudging back to their villages.

Yet some online outlets, and media watchdog groups, say they, too, work under the growing threat of prosecution, including for defamation (a criminal offence in India), sedition (a crime dating back to colonial rule) “incitement of hatred” or other charges. While many leading online news outlets are based in Delhi, the legal cases and investigations, which journalists describe as “harassment”, most often come from police, companies or individuals in India’s states.

Journalists say they have been investigated after covering stories that touched a nerve, including last year’s protests by farmers against proposed agricultural reforms — a rare public setback for the government.

“This is something unique to Modi’s administration: the use of ordinary criminal law against media or journalists’ platforms for stories they have done, or social media posts,” says Siddharth Varadarajan, a founding editor of news website The Wire. The outlet has faced a string of defamation suits and other charges, including five filed by police in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, ruled by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party.

In early 2021 after covering police violence at the farmers’ protests, The Caravan, a monthly magazine based in Delhi, faced 10 sedition cases in five different states (four of which are BJP ruled), filed against its executive editor Vinod Jose and its owners, Paresh Nath and Anant Nath. The cases are still outstanding, but India’s Supreme Court has granted all three bail.

“This seems to be the script,” says Jose. “They try to target journalists, public intellectuals, or human rights activists on the ground raising issues of civil importance, then book them on a case and send in the agencies, who are being weaponised against anyone who is working critically in the space of democracy.”

Journalists, particularly those operating outside the relatively elite confines of the English-language press, have valid reasons to fear for their personal safety. In 2017 Gauri Lankesh, a prominent critic of Hindu nationalism, was shot dead near her home in Bangalore. She had been convicted of defamation in 2016.

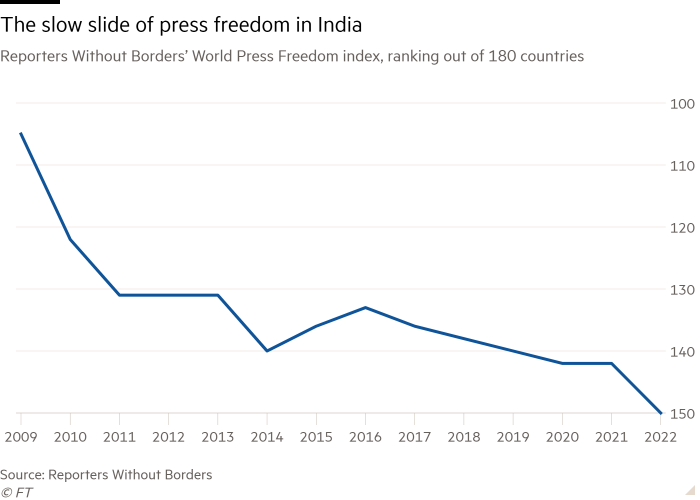

“On global indices, India has regressed considerably in terms of social, political and economic freedoms over a long period of time,” says the IFF’s Gupta.

The most recent World Press Freedom index from Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked India 150th out of 180 countries worldwide, down from 142nd the previous year. With more than 100,000 newspapers and 380 TV news channels, RSF described India’s media scene as “a colossus with feet of clay”.

Gupta believes the increased scrutiny on tax compliance at Indian NGOs will take a further toll: “These organisations don’t have the funds and resources for sophisticated compliance, which includes expert advice from chartered accountants and financial planners.”

Silenced voices:

Government critics say the core Indian values of diversity and secularism on which the republic was founded are now under threat — and, with them, talented citizens’ opportunities to rise to leadership roles.

“We know this from history: that the people who led inventions and innovation were immigrants, minorities, kids with curiosity,” says Jose. “What we are now doing as a country to our own people is killing all the opportunities for people of very diverse backgrounds to emerge and excel.”

Several of those ensnared in legal cases in recent years have been Muslims. In a country where the BJP’s majoritarian Hindu nationalism has widespread support, public anger whipped up by online commentators has played a role in punishing outspoken minority voices.

When Zubair was arrested in June, the journalist and fact checker was charged with “hurting religious sentiments and inciting riots”. The arrest, which followed a sustained online campaign, was made in connection with a 2018 tweet in which he had posted a still from a 1983 Bollywood film, which was interpreted by some as insulting to Hindus. A widely shared tweet offered cash rewards to anyone who could file police complaints against Zubair and Alt News, arrest him, or convict him to a jail sentence.

Police seized Zubair’s laptop, mobile phone, a hard drive and tax invoices during a search of his house, although his lawyers pointed out that the devices were not needed to investigate tweets. He was released on bail after several days in detention. He still faces multiple outstanding legal cases in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

But Zubair’s lawyers believe the real reason for his arrest was another tweet in May in which the journalist published offensive remarks about the Prophet Mohammed made by a then-BJP spokesperson Nupur Sharma. The remarks created a furore in some Muslim-majority countries and Sharma was suspended from the ruling party, which denounced her comments.

Another Muslim journalist, Siddique Kappan, was arrested in 2020 while travelling in Uttar Pradesh to cover the rape and murder of a Dalit woman. India’s Enforcement Directorate, an agency under the purview of the ministry of finance that is responsible for investigating economic crimes, filed a case against him and four others last year; police accused him of seeking to incite religious hatred and of having links to the Popular Front of India, a Muslim group that India outlawed in September after accusing it of having links to terrorism. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court granted Kappan bail after almost two years’ of detention, but he remains in jail on a separate charge.

Munawar Faruqui, a Muslim comedian, was arrested during one of his shows last year, under India’s hate speech laws, by police in Indore in the state of Madhya Pradesh. The arrest came after public accusations that he was making jokes about Hindu gods and goddesses and ruling officials.

“There is a serious push through the political process to divide the people of the country, and it is succeeding,” says Grover, the human rights lawyer. “India has always had strong institutions that can withstand majoritarianism, and which made us distinct from our neighbours. But what we are seeing today is the independence and robustness of these institutions is being compromised and abridged.”

The new normal:

Gupta, the information ministry official, says the government’s critics are guilty of lazy attempts at demonisation. “Contrary to what some people think, the Modi government doesn’t have two horns and a tail,” he says. Of Modi himself, he adds: “he’s not a prime minister who is on the think-tank circuit or with the chattering classes.”

The observation echoes the BJP’s broader anti-elite ethos, which seeks to paint its rival Congress as a party of corruption and cronyism. Having handily won two elections on the promise of sweeping away the old guard, the BJP government can rely on supportive social media channels teeming with enforcers of the new norms.

“One of the biggest assaults is on the credibility of journalists,” says Srishti Jaswal, a reporter who comes from a Hindu family, lost her job at a national newspaper after a social media furore. “If you criticise Modi, people don’t believe you . . . Journalists eventually become a non-credible voice because of the trolling that happens online.”

In 2020 Jaswal was suspended, and then resigned, from the Hindustan Times, a leading English-language paper, after online critics unearthed a tweet in which she had made a flippant remark that was widely interpreted as an insult to Lord Krishna. OpIndia, a rightwing portal that frequently attacks what it sees as the enemies of Hinduism, denounced her as a “Hinduphobic journalist”. It accused her of “vile social media posts making abusive rants against Hindu deities”.

She now faces an ongoing case in a court near Delhi — an offence that could carry a three-year prison sentence. Yet, she says, online critics had earlier taken offence at a poem she had posted about Jammu and Kashmir, the majority Muslim territory that the government stripped of its status as a state after winning re-election in 2019.

“My reporting was in focus, but they could not find anything objectively wrong with it,” she says. “However, it was easy to take my tweet out of context.”

Jaswal says the legal threat is only one aspect of her ordeal. She adds that the space for free expression is increasingly being policed, not only by the government itself, but also by an army of supporters of its ideology who are using “extremely sophisticated software” to abuse journalists online. After the tweet was highlighted, she says she was hounded by thousands of strangers online, including in the form of “rape threats, death threats and pornographic content”.

“I was in the middle of the worst abuse,” she adds.

Jaswal says she is now undergoing a digital security course in an attempt to safeguard herself against such attacks “because I am scared . . . I am scared of what’s to come.”